It’s in the blood for Dean

Dean Higgins is third-generation of a Marlborough family involved in the

mussel industry since well before the farming of the species began.

His parents, Albie and Raelene who still live in Blenheim, used to handpick

mussels in the Kenepuru and Nydia Bay (for Norman Wells) in the mid-1960’s.

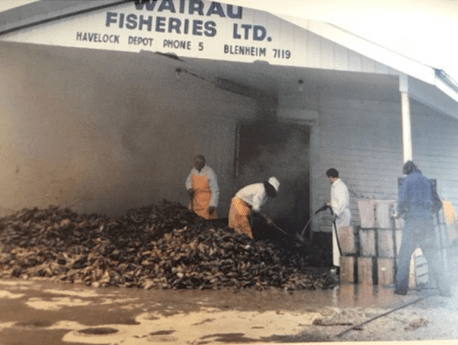

And his grandfather on his mother’s side, Tom Slape, occasionally worked

for Winston Pickering who started Wairau Fisheries in the 1960s, processing

and cooking wild mussels.

So, it’s no surprise that as a fifteen-year-old, the night shift at Sanford’s

Havelock factory was Dean’s own introduction to a 35-year career in the

seafood industry, mostly centered on greenshell mussels.

He’s enjoyed just about every day of it and established friendships that have proved life-long.

Dean worked on the Sanford processing line in 1986 as a fifth former at Marlborough Boys College during the holidays as well as some night shifts.

The following year he left school and joined the permanent staff.

“I did just about every job in the factory apart from cooking.”

But his eye was on the mussel boats bringing in the sacks every day to the factory.

He approached Chris Godsiff, then managing operations for Sanford, who put him on top of the list.

“Two weeks later he tapped me on the shoulder when I was opening mussels and said: I’ve got a job for you.”

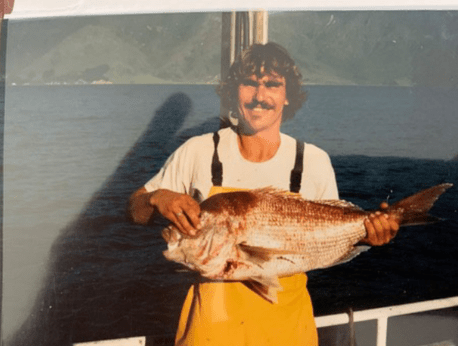

He joined the Wait Iti at age 18 as a deckhand, serving with Vaughan Ellis as skipper.

“It’s a book in itself the adventures I had with Vaughan".

The industry was just beginning, and we had a lot of fun. One of our proudest achievements was developing and catching the first commercial quantities of local spat in Pelorus Sound.

Don’t get me wrong, people had been catching spat before us, but we were first to catch huge volumes for commercial scale operations.

"Back in those days we caught so much spat we couldn’t use it all.”

They also worked ridiculous hours.

“One time we worked three days straight without stopping. I’ve seen grown men falling asleep standing up on many occasions.”

When Dean was 21, Vaughan was offered a management role at Sanford and told Dean the first-ever skipper’s course in Picton was about to be held:

He said: “You’re starting it next week.”

It was four intensive weeks with the exams held on the final Sunday.

“If I passed, I was taking a boat out on Monday; if not, I was back as a deckhand,” says Dean.

Only two out of 18 students passed the course and Dean started the week as skipper of the San-Tai.

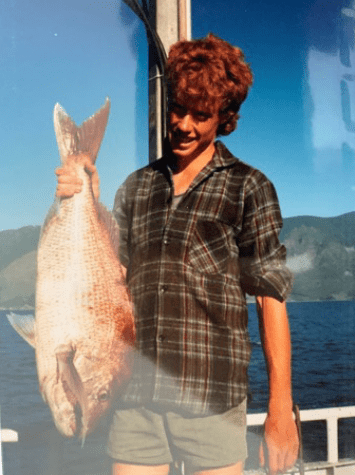

After a few years at the helm in the early 90s, Dean decided to try his hand at inshore fishing. This included surface long-lining out of Bluff, catching hoki in Cook Strait and chasing albacore tuna off the West Coast.

But he missed the mates and the mussel industry and returned in 1998 to a skipper’s role with Marlborough Mussel Company, owned by the Yealands family, and Vaughan Ellis turned up not long after in a management role.

It was soon bought by Pacifica and after a year Merv Whipp took over running the operation.

He asked Dean if he’d like to take on a job in management assisting Vaughan.

“I came off the boats and got trained up in management. Merv was awesome to work for.”

Pacifica’s mussel business was sold to Sanford in 2010. Vaughan had gone overseas and Dean joined Kono which was then expanding. Merv had gone to Ngai Tahu and lured Dean across.

After a couple of years, Ngai Tahu decided to sell its aquaculture division and it was bought by Kono.

“So, I boomeranged back to Kono.”

He’s been there ever since and now is Operations Manager across Golden Bay and the Pelorus.

“I’ve worked for a lot of different people and it’s given me a good overview of the industry. There’s not many mussel farms (in the top of South) I haven’t visited.”

That included a lot of diving back in the day which confirmed for him the wider benefits of mussel farming beyond being a sustainable source of fantastic food for the world.

“Every mussel farm is a mini marine reserve. Every time I dived underneath a farm it was just teaming with life. You’d go off the farm and it was just mud with nothing happening.”

Mind you, diving under a farm almost cost him his life.

He and a buddy were in Crail Bay in the mid-90s, searching for a block which had dragged

in on a mussel line. Dean hadn’t checked his air gauge after a first dive attempt.

The block had gone down into a trench and Dean discovered he was at 147 feet down with no air left.

He credits his diving buddy, Aaron Williams with saving his life by sharing his air through a rapid ascent. They surfaced with blown out noses and ears and masks full of blood.

“No one could understand why we didn’t get the bends.”

Dean stopped diving after that but there was no shortage of other hard physical work. He was part of an effort to grow scallops on lantern trays and there was always the mussel harvesting, much of it involving manual effort.

“If you processed 10 tonne in a day the boss would shout you a beer at the pub.

We do that now in minutes. We had no hiabs on the harvester; it was pallets and a pallet jiffy to move one tonne bags around the deck.”

While technology has moved on hugely, Dean says it’s still developing and needs to as nature is always going to throw curved balls.

“You’re always worried about having enough spat, how are they going to grow and perform. We’ve only been marine farming for about 40 years. They’ve been working the land for thousands of years. We are still breaking new ground every day.”

“While it’s been amazing to watch and be involved in the innovations and improvements that have been made in the industry, if 35 years of mussel farming has taught me anything, it’s that people are the most important asset to any operation; having the right people, passionate about what

they do, fully supported and looked after, will make any business succeed".

Dean is now a member of the Marine Farming Association Board and is helping guide the future of the industry in the top of the south.

Contact us

Phone: 03 578 5044

Physical address:

Ground Floor - WK Building

2 Alfred Street

Blenheim

Postal address:

PO Box 86

Blenheim 7201